Preface: Brave New, Old Worlds

Herewith all the works in the book>>

‘War is the father of all and the king of all.’ Thus, once, spoke a famous Greek philosopher. We, contemporary (modern or post-modern) human beings experience the truth of this utterance day-in day-out, on television and on the internet. Over and over again we are being confronted – or so we believe – by the truth about war, wherever it may be happening in the world. The newscaster reads it out to us: here (on this channel), and now (only now at this very moment), we bring you the true horrors, the real events, the facts, the truths. Surely you are familiar with this?

Seldom do we have time to reflect on those words that we hear day-in day-out on television, on the world wide web, on the radio; or that we read in the newspapers. We have become so accustomed to hearing these hollow phrases that make us believe that what we are being fed by the media is, in fact, the only reality, the true story, so that we – the ‘loyal viewers’, as they call us – do no longer bother to ask ourselves: What do you mean: the true facts? What do you mean: the real story of the war? Whether it pertains to the ever-lasting conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, the so-called war against terrorism, the assaults in New York, London, Madrid or Bali – the newsreaders keep telling us: these are the facts.

In other words, what happens over and over again, in an endless wave of news images: we – all of us collectively – are meant to identify ourselves with the images that are being flashed in front of us. No questions, no thoughts – the System prescribes that there be no room and, especially, no time for reflection.

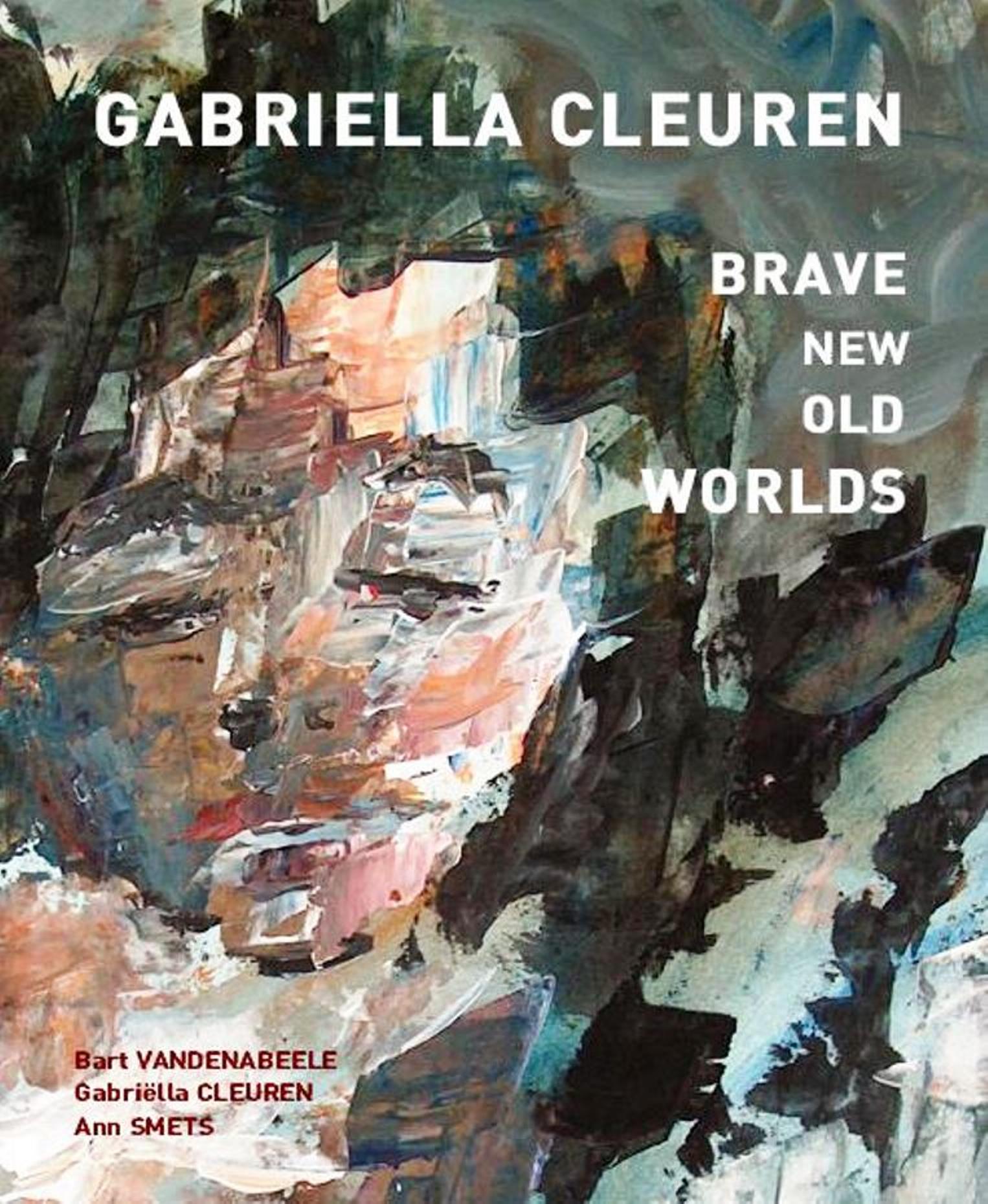

No greater contrast can possibly be imagined than with the way in which painters, such as Goya, Ensor, Karel Appel and Gabriëlla Cleuren offer us their images, their forms, their colour touches and subtle nuances – in brief, their artistic gestures. What is true of Goya’s Desastres de la Guerra, certainly also holds for Gabriëlla Cleuren’s sublime series: it yields an exquisite critique of the dominance of the manner in which images are mostly being treated. What the ‘format’ of the TV newscasts dismisses (due to lack of time, as they call it), is exactly what Cleuren’s work demands. These works demand time, they dismantle the prevailing Hollywood ideal and the grinding fictions that are imposed upon us: moments of violence and horror, which affect our very soul. They do not just appeal to a quick moral reaction by the simple TV-spectator, who briefly shudders at the painful images of Chechnyan war casualties or African people dying of famine – indeed, they stir within us something else; a capacity that these days is given rather short shrift in place and time but that nonetheless slumbers in all of us.

I mean our capacity to be touched and moved by the genuine power of the forms and the colours in art, by Cleuren’s images that tell us not only about war and conflict, about injustice and inhuman suffering – as is the media’s custom – but express them in such a way that we can no longer merely identify ourselves with them, for they totally disrupt our imaginative capacities through their energetic interpellation. Our thought processes are momentarily being unsettled and upset by Cleuren’s works: we are, as it were, paralysed; we feel inadequate against the power of so much colour and masterful technique. We become – whether we like it or not – affected by the chromatic conflicts we see and experience here. It is not our capacity to absorb knowledge (which is crucial in the processing of information) but rather our imagination that is being challenged and disrupted here; by the dynamic that emanates from the subject matter, our imagination becomes unsettled, and it is overwhelmed by the materialised aggression and the outrage that drips from the canvasses. However, after the expression of the Dionysian violent frenzy, enters the Apollonian dream, bringing with it also the critical distance which allows us to scrutinize again and again, to contemplate and to participate in the mysterious (but not mystical) imagery of Cleuren’s magnificent oeuvre.

Cleuren’s masterful art work demands – entirely opposed to the spirit of our time – time for viewing, yes, a lot of time. One may immediately become aesthetically moved and touched, and also frequently unsettled, but it is only through repeated scrutiny of Cleuren’s work that its true critical potential will be revealed – an oeuvre, which not only embarks on a dialogue, but also a dispute with the works of Goya, Ensor, and many other great painters. Moreover, it also – sometimes hopefully, mostly desperately – adds a new dimension to contemporary art, which often (due to a misplaced aestheticism) refuses to concern itself with the social and political aspects of our human (or inhuman) existence.

War is indeed the father of all… Gabriëlla Cleuren’s work demonstrates that she, as an artist, is the mother of this father; and by her subtle use of splendid colours, powerful compositions and fascinating nuances she lets us linger for a while over the monstrous aspects of an inhuman, all too inhuman, world.

Reacties

Een reactie posten